Constructing

a unified identity

within the

iranian diaspora

2020

Introduction

by Daria Karraby

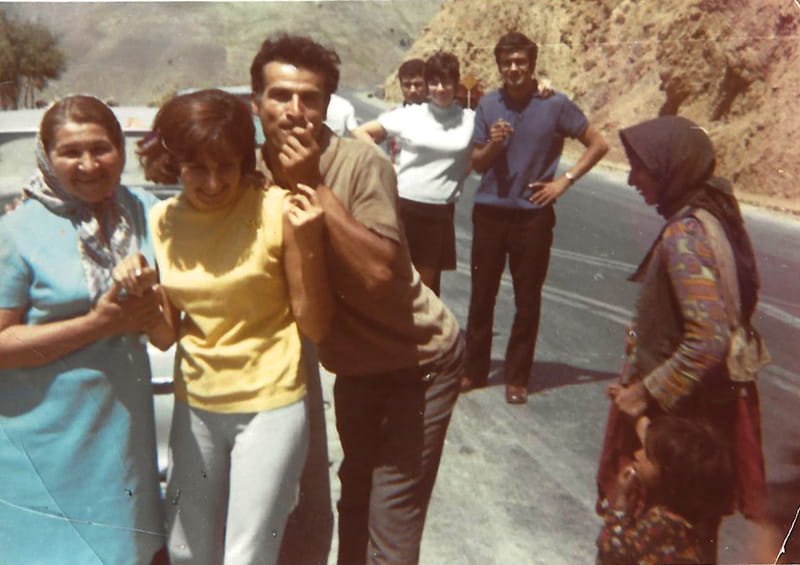

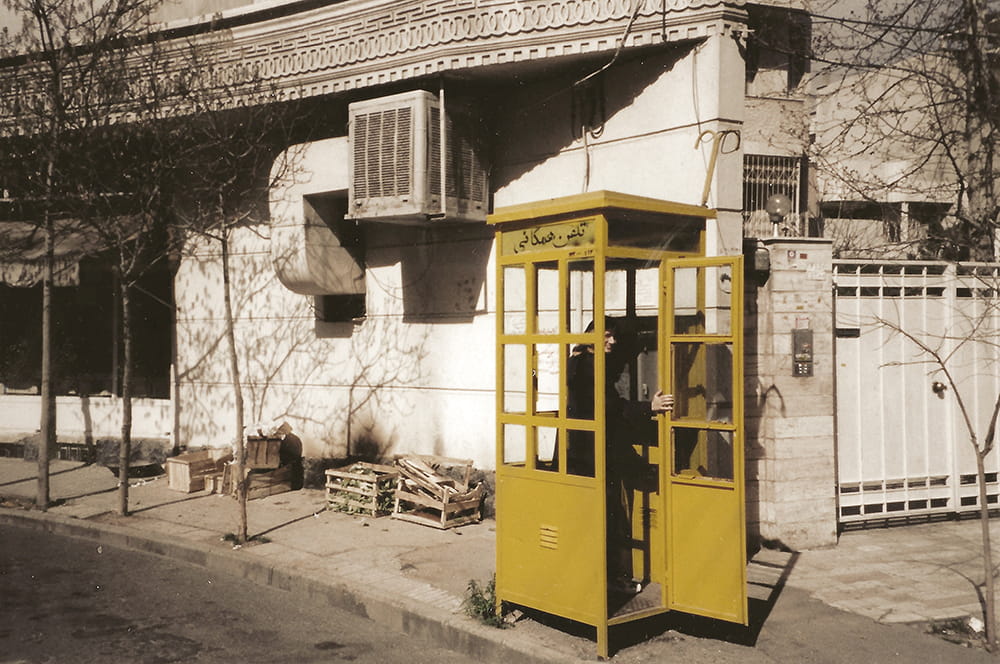

My parents had no hopes for an American dream. Even more, they had no desire for it. They had rich, full lives in their homeland of Iran. The streets of Tehran was their playground. They spent their summers splashing in outdoor pools and gorging on saffron ice cream. They attended at least one party a week, dancing until the wee hours of the morning. My father came to Philadelphia to study engineering because that was just the thing young, middle-class Iranians did. Go to America, study some, have your fun, and return home with a diploma in hand. My mother was attending a girls’ college in Iran, but, when the initial tremors of the Revolution hit, school was hardly ever in session. Her parents sent her to the east coast of the United States so she could complete her education without any distractions. America was never the end goal. It was a detour, a fun vacation stop on the path to a brighter, distinctly Iranian future. My parents could not have foreseen that this detour would turn into a permanent stay. I should not exist. Without the Revolution and the destruction of the Iran of my parent’s childhood, my mother and father – my Maman and Baba – would never have met.

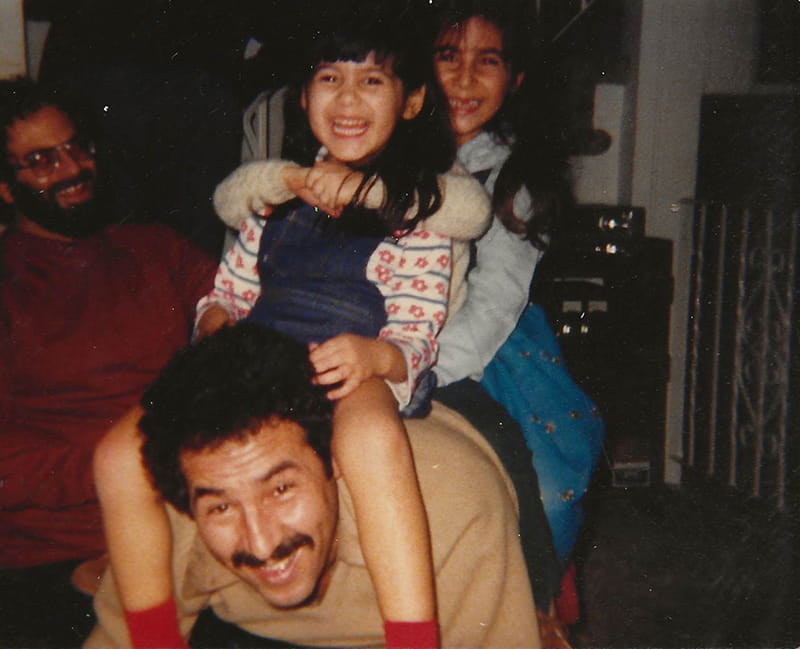

My parents forged a makeshift version of their own childhood for my sister and me, the so-called first-generation, here in America. Our parents signed us up for cultural dance classes with teachers who were also Iranian immigrants. They enrolled us in Farsi language courses. They surrounded us with other Iranians and their children and, together, we all formed a kind of tribe. We spent both Iranian and American new years together, attended each other’s birthday parties practically every other week, and went on annual summer camping trips.

I could not always remain in this utopian world my parents so carefully crafted. As time went on, I began to visit only on the weekends, whenever there was another party or gathering. I would only ever fully immerse myself in this Iranian world in the privacy of my home. At school and in the company of friends, I was just like any other American teen. I went to the mall on the weekends and only listened to top forty music. As I grow older, I find that I can no longer hop between these two worlds so easily. I can no longer keep these identities – the Iranian and the American – separate. (Perhaps, I never did.)

As tensions between Iran and the United States continue to rise, I find myself reverting to old patterns. I refer to myself as Persian, wary of the implications claiming the identity of Iranian will have. I hesitate to speak Farsi in public, afraid of attracting suspicious eyes and ears. In private, I ask my family to retell stories from their Iranian childhood, hoping I can leverage them to construct some semblance of an ethnic identity for myself. There are two stories to tell, the story of our parents, and then of us, gifted with and suspended between two worlds.

at the

edge

of society

edge

of society

the

unrooted

iranian

self

unrooted

iranian

self

The Iranian revolution of 1978–1979 globally dispersed an enormous number of Iranians from all walks of life. The Iranian Hostage Crisis of 1979–1981 incited anti-Iranian sentiment throughout the USA.

1979

by Anonymous

My memory

of this time period was nothing more than a 16 year old teenager looking forward

to an unknown adventure in the States, and Disneyland.

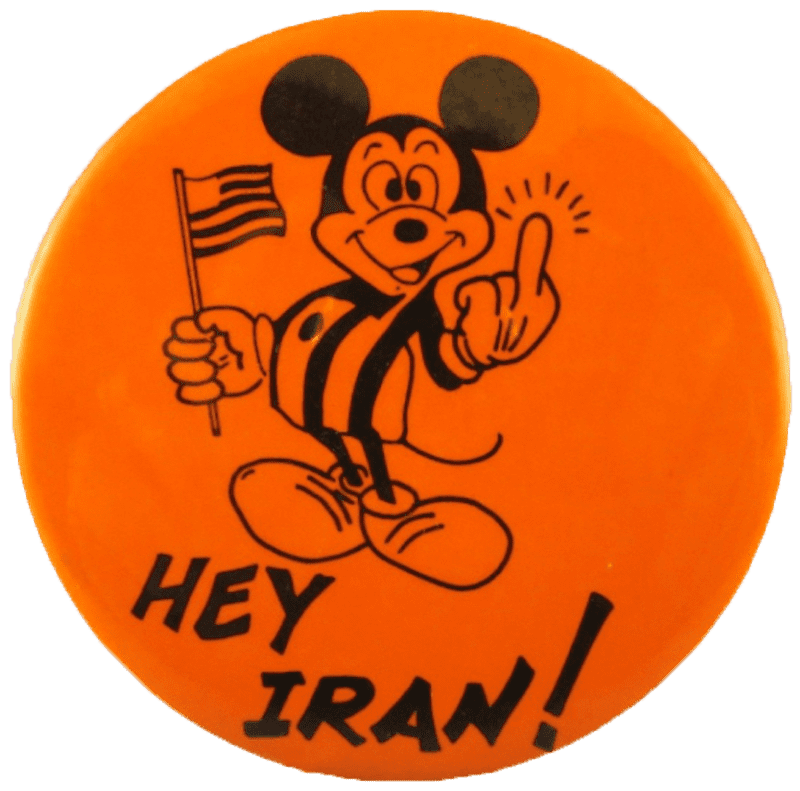

But, in those days, People made T-Shirts and images of mickey flipping OFF Iran and Iranians.

Go figure, I came to see him in his castle, and he flipped me. That's one for the books. I learned what it was like to be hated, believe it or not, that’s a skill.

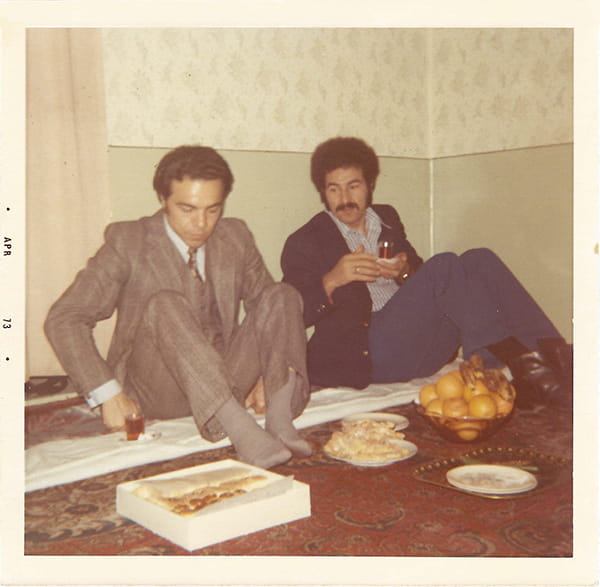

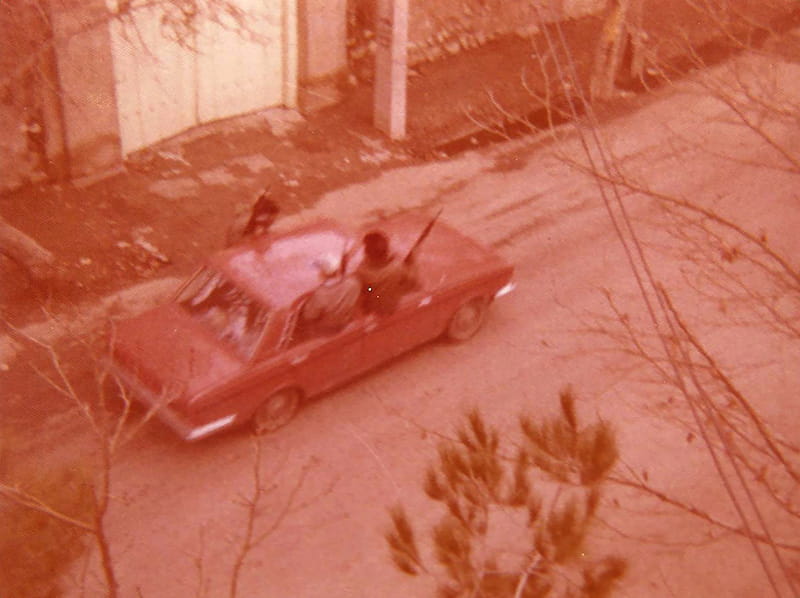

In 1979, I am 16 and Iran is experiencing social unrest. We just moved from Tehran, where I lived for the past 6 years, to Isfahan where I was born. The unrest by this time is visible in our daily life, in forms of demonstrations and gatherings. Looking back at this time period, I came to find out that my parents sent me to America to study for the sake of my advancement and safety, and due to their fear of the unrest.

While in the USA, the Hostage Crisis started to unfold. School/education became secondary, and survival is now a reality that can not be ignored. I started working full time to support myself. A couple of years into this decade, the Iranian government convicted my father and fired him from his job because of my participation in a rally in the US. I came to find out that they somehow got hold of a picture of me standing in the streets of San Francisco watching a rally. This harsh reality hit me hard and left me helpless. Now here I am, a teenager with no country. I couldn’t go back for fear of persecution, and couldn’t stay here because of no status. I did what I thought was the best course of action and applied for political asylum.

1989

I’ve been in the US for the past 10 years. In retrospect, I don't think I was sent to the US with preconceived plans for migrating. I think my parent’s thought I would be safe while studying, graduate and go back home 10 to 12 years later. I have to admit the past 10 years have definitely been an experience that has shaped who I am today. America was the only choice my parents had, because of our existing relatived who were already students here. Iran, at this point, was in full blown revolution that came with its own unique circumstances. The initial vacuum of revolution created social stability, freedom of thought, speech and equal social justice. However, sadly, it didn't last more than six months or so before the Mollas took over. During those initial six months, most Iranian students in the US and abroad saw this vacuum, and concluded that they should go back home and contribute, against their parents’ wishes. Soon after, a close friend and I found ourselves all alone in a two-bedroom apartment in downtown San Jose. He was a senior in high school and I was in the 9th grade. About a year into this, the source that our parents used to send us money was cut off.

At this point, school and academics were definitely on the back burner. I took classes here and there, focusing in Photography and Industrial Design. By the mid-90s, I was fully integrated into US social life and employed. By the late-90s, I had met my ex-wife and, at around that same time, my Dad, Mom, and sister fled from Iran and joined me in the US.

I am the interpreter,

the cultural bridge

— Dumas

2020

Children of immigrants in America have a shared experience that connects us. Many of us live between different, and often clashing, cultures. I have spent most of my life finding a balance between being both Iranian and American. This duality is both displacing and liberating. It can be a source of both pain and joy that is uniquely ours. My parents and their friends took the best of Iranian culture and society, and used it to create a richer world for their children in America.

Introduction by Daria Karraby, Design by Hanna Karraby , Dev by Maximilian Berndt , Text and Research: “Constructing Identity in Iranian-American Self-Narrative” by Maria Wagenknecht

2020